MONDAY MOVIE REVIEW: Django Unchained

You can guess: critics and pundits will decry it for excessive violence and use of the n-word.

The irony is that, for once in his career, Tarantino isn't embellishing. At least not where it counts. Because the gruesome reality of slavery is "uncomfortable and people would rather avert their eyes," Tarantino says in an interview with the Miami Herald, "America has conveniently chosen to avoid dealing with it."

So, the fun of some of Django's most offensive scenes, Roger Ebert explains, "may be because the audience expects to see violence but doesn't expect to get it at such an extreme; he's rubbing it in." If you're in on the joke while you're still in your seat, it's very meta. If you're not, you're part of the problem.

Tarantino is being both funny and deadly serious. He made Django to say, "This is us. This is how this country was founded." And to shatter an American taboo: the Southern Code of Honor.

The Very Heart of America

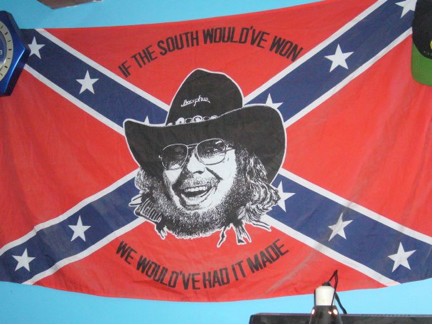

There's a Hank Williams Jr. song, If the South Woulda Won. "We'd a had it made," Bocephus sings, "We wouldn't have no killers gettin’off free/If they were proven guilty, then they would swing quickly." He also promises to ban all cars from China, "take Miami back," and make the day Elvis died a national holiday.

American culture has always romanticized the antebellum South. In history books, in movies from Birth of a Nation to Gone With the Wind, in the Dukes of Hazzard, in more recent country songs, we've carried a tradition since the Civil War called The Lost Cause of the Confederacy. The gist is the South died nobly in defense of a good cause, their home and their rights, and old-fashioned chivalry.

In 2013, with Barack Obama in the White House, that revisionist history has almost died off, but where the Lost Cause holds sway is in our culture's idea of what it means to be a man.

In a classic book, W. J. Cash described 'the South at its best': "Proud, brave, honorable by its lights, courteous, personally generous, loyal and swift to act." Values embodied in the the Southern Code of Honor, 1838 rules for dueling.

Without a sense of when justice might be too swift, without knowing what's hidden beneath a culture of honor, we have largely embraced these values as the archetype for American manhood.

So Tarantino made Django to open up the antebellum South, "to go there, and take a look at America."

Jane Goodall Meets John Brown

In Django, Tarantino shows us the white porticos, the Spanish moss, the little white balls of cotton – and splatters it all in blood. Because it was splattered in blood. He's not showing us simply that "slavery was bad;" he's showing that nothing about antebellum society could be good.

Like on some antrhopological safari (that's mostly historically accurate), Tarantino catalogues the whole Southern ecosystem: the planation owners, the armed posses, the slave auctions, the lawyers who authenticated the ownership papers, the battles royale (which Tarantino calls Mandingo fighting), the comfort girls, the Uncle Toms, the KKK, the phrenology used to justify it all, the dogs...

Calvin Candie: Your boss looks a little green around the gills.

Django: He just ain't used to seein' a man ripped apart by dogs is all.

Calvin Candie: But you are used to it?

Django: I'm just a little more used to Americans than he is.

IMDB

It's not some figurative moral taint Tarantino is evoking; he's scientifically exposing the mechanisms needed to keep human beings as livestock.

He disects the South. He slices it open and shows us a cross-section of plantation living. Like looking into a dollhouse, we see the ornate dining room, the fine china and linen. But while the genteel ladies and menfolk are having their polite dinner conversation, an armed posse is pointing guns at half the people in the room. That's the only way a society based on subjugation works: by lethal force.

My only criticism of the movie is this feels didactic. As other critics have noted, Tarantino takes his time with the tour, stopping long enough at each inescapable perversion of slavery to make sure we're horrified before moving on. "Something happens to the pace and the poise of Django Unchained as the hunters head South," Anthony Lane at the New Yorker writes.

But about two-thirds of the way through, Tarantino remembers he's tresspassing in the South, and picks up the pace.

He leads us on an armed raid, like John Brown. And his weapons are:

- Music: The soundtrack mixes 2Pac, James Brown, Beethoven, John Legend, Rick Ross and Ennio Morricone;

- Cinematography: Many of the exterior shots are expansive and overexposed, making us feel the oppressive heat of the South;

- Laughter: Tarantino will make you cringe at the lash in one scene, and laugh at it in the next. And there's a scene about KKK hoods that's straight out of Loony Toons;

- Villains: A common device of abolitionism was drawing attention to how perversely slaveholders enjoyed owning human flesh. Tarantino rubs your nose in it;

- ...and of course, weapons.

It's not much of a spoiler to tell you the movie ends in an orgiastic shootout, but this might be: By the end of Django Unchained, Quentin Tarantino literally explodes with moral indignation.

He obliterates the South. As the blood gushes and the bodies pile up, you glimpse the senselessness and the inevitability of so much violence. (The subtitles tell us the movie takes place "two years before the Civil War.")

Lane at the New Yorker chides Tarantino for only being interested in "simple comeuppance, issued with merciless panache," but Tarantino's not just tearing down the antebellum American ideal; there's something else he's doing.

He Builds Up a New Black Hero

At some point in Django Unchained, you're going to see Jamie Foxx's penis. This is the second American taboo Tarantino breaks: the potency of black manhood.

In our culture, most black male characters don't get to be heroes. Typically, they conform to a handful of stereotypes, either good or bad: Sambo, the black brute, the Magical Negro, Uncle Tom, the BBF. And, as A. O. Scott points out in his brilliant New York Times review, the role of the vengeful hero (think The Punisher or Dirty Harry or Liam Neeson in Taken), which is the dramatic expresion of the Southern Code of Honor, has been forbidden to black men.

(The exceptions in film, Shaft and blaxploitation, are referenced heavily by Tarantino's entire oeuvre. In fact, you could view Tarantino's career as an ongoing effort to give the role of vengeance that white men have reserved to themselves to women, Jews, black men, and anyone who needs a new hero.)

But Django isn't just a black badass like Shaft, he's driven by love for his wife. By his goodness. Separated from his wife, he journeys across the South to rescue her. He's a family man.

When Jamie Foxx joked that he got to kill white people in this movie, some conservative bloggers freaked out. When, in a screening of Django, the audience laughed at his character shooting a white woman, Anthony Lane was "disturbed."

You're not in on the joke, Anthony!

Much of the Southern Code of Honor – swift justice and silence; distrust of outsiders – was built around the fantasy of defending white women from the rapacity of black men. In Django Unchained, Tarantino uses the mythmaking potential of the Spaghetti Western to un-geld the black man. Django has to shoot her, and we have to see his dick, or the whole project doesn't work.